Comprehensive Overview of Rheumatoid Arthritis: From Symptoms to Prevention

Table of Contents

Introduction

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own joint tissues, especially the synovial lining (synovium) of joints, leading to inflammation, pain, stiffness, and eventually joint damage.

Unlike the more common degenerative form of arthritis, Osteoarthritis, which mainly results from mechanical wear and tear of cartilage, RA affects the synovial membrane, causes joint inflammation, and may lead to bone erosions, cartilage destruction, and joint deformities.

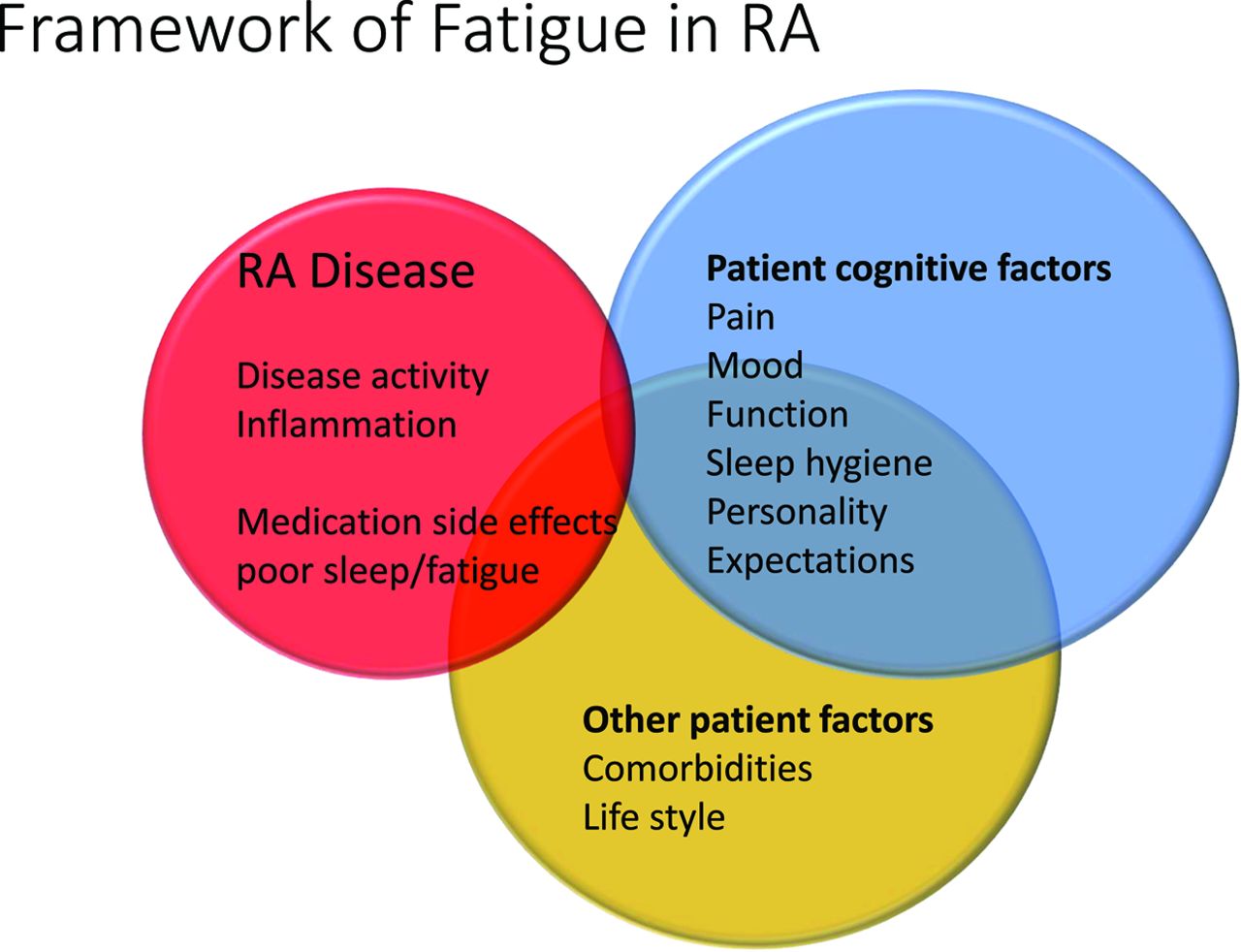

RA is not just a “joint disease” — it is systemic, meaning multiple organs can be involved, and its impact is both physical and psychosocial, affecting quality of life, function, and longevity.

In this article we will review its introduction, key symptoms, causes and risk factors, how the diagnosis is made, the main treatment approaches, and strategies for prevention or risk reduction.

Symptoms

Early and typical joint symptoms

The hallmark joint symptoms of RA include:

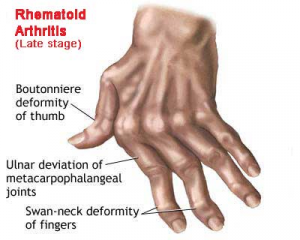

- Pain, tenderness, swelling and warmth of the joints — often beginning in the small joints of the hands (metacarpophalangeal & proximal interphalangeal joints) and feet (metatarsophalangeal joints).

- Morning stiffness or stiffness after periods of rest or inactivity, often lasting more than 30–60 minutes, and sometimes hours — a feature pointing to an inflammatory arthropathy rather than simple wear-and-tear.

- Symmetric involvement: RA typically affects the same joints on both sides of the body (for example, both wrists, both knees).

- A gradual increase in the number of joints involved (polyarthritis) though some cases begin more rapidly.

- Decreased range of motion, stiffness of movement, difficulty gripping or walking when hands/feet are involved.

Systemic and extra-articular symptoms

Because RA is systemic, symptoms often extend beyond the joints:

- Generalised fatigue, malaise, low-grade fever, weight loss or lack of appetite. These symptoms may be subtle but contribute significantly to overall burden.

- Rheumatoid nodules: firm lumps under the skin (commonly over pressure points like elbows) in some individuals — especially those with more severe disease.

- Extra‐joint organ involvement: RA may affect skin, eyes (e.g., dry eyes, scleritis), lungs (interstitial lung disease, pleurisy), heart (pericarditis, accelerated atherosclerosis), blood vessels (vasculitis), and nerves (entrapment neuropathies).

- Flare and remission pattern: Many people experience periods of increased disease activity (“flares”) alternating with times of relative quiet (“remission”).

Progression and complications

If left untreated or poorly controlled:

- Joint erosion and deformity: bones and cartilage are damaged; joint alignment may shift (for example ulnar deviation of fingers) and function is lost.

- Loss of mobility, reduced ability to perform daily tasks, impairment of work and social life.

- Increased risk of comorbidities: osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, lung disease, infections due to immune-modulating treatments.

Causes and Risk Factors

Underlying mechanism

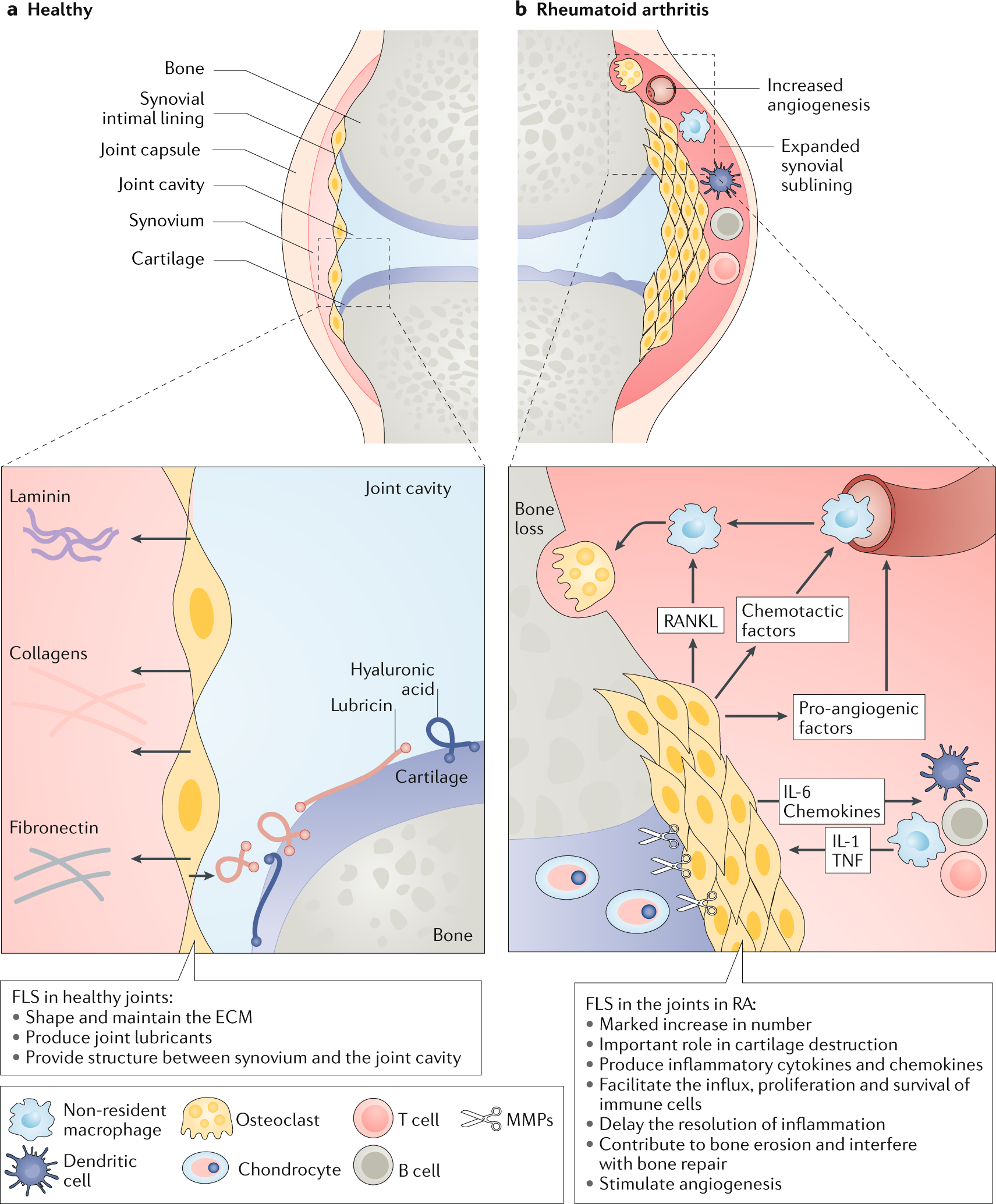

The exact cause of RA remains not fully understood, but it is considered an autoimmune condition in which the immune system becomes dysregulated, attacks the synovium (joint lining), and propagates inflammation.

Key aspects:

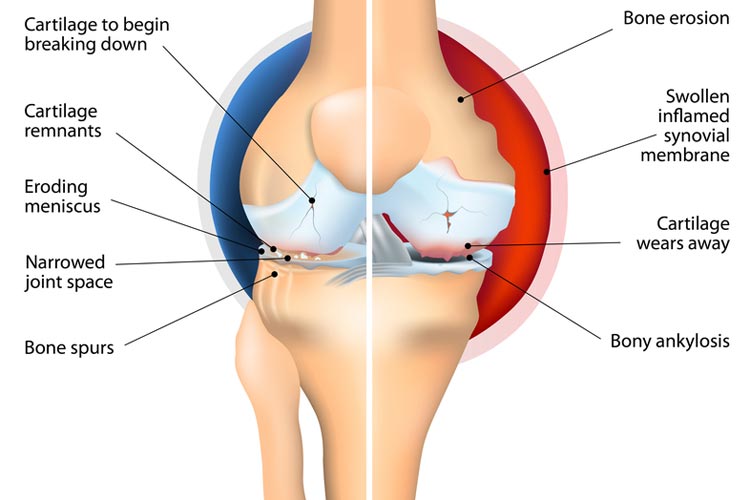

- The synovium becomes inflamed (synovitis); the inflammatory cells release cytokines and mediators that directly damage cartilage and bone in the joint.

- With time, persistent inflammation causes bone erosions, cartilage destruction, and may cause the joint to collapse or subluxate.

- There is an interplay of genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and immunologic abnormalities.

Risk factors

While the precise “trigger” may vary, several risk factors for RA are recognised:

Non-modifiable risk factors

- Gender: RA is more common in women (roughly 2–3 times more likely) than men.

- Age: Although RA can occur at any age, it often begins between ages 30 and 60.

- Family history & genetics: A family history of RA raises risk; certain HLA (human leukocyte antigen) types (e.g., HLA-DRB1 “shared epitope”) are associated with increased susceptibility.

Modifiable and environmental risk factors

- Smoking: One of the strongest modifiable risk factors: smoking increases development risk and severity of RA.

- Obesity and excess weight: These increase inflammatory burden and may raise the risk of RA as well as worsen outcomes.

- Periodontitis and gum disease: Emerging evidence suggests an association between chronic gum inflammation and RA onset. (While less conclusively established, it is recognized in some literature.)

- Other environmental triggers: These may include certain infections, exposures to silica or certain dusts, hormonal factors—but definitive causation is less clear.

Why prevention is complex

Given that underlying causes include genetics, immune mechanisms, and environmental exposures, preventing RA entirely is challenging. Instead, attention focuses on identifying high-risk individuals and modifying risk factors where possible. Early detection and treatment are equally important to prevent damage once disease is triggered.

Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation

Diagnosing RA involves a combination of clinical history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and imaging. There is no single definitive test.

Key steps:

- Taking a detailed history: pattern of joint pain, morning stiffness, symmetry, duration, systemic symptoms (fatigue, low-grade fever).

- Physical exam: examination of joints for swelling, warmth, tenderness, range of motion; looking for rheumatoid nodules; checking for extra-articular manifestations.

Laboratory tests

Useful blood tests include:

- Rheumatoid factor (RF): an antibody present in many, but not all, RA patients — positive in ~70-80% of cases.

- Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies: more specific for RA, may appear early.

- Inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) often elevated, indicating systemic inflammation.

- Other tests: complete blood count (CBC) (often shows mild anemia of chronic disease), metabolic panels, liver/kidney function (especially to monitor before treatment) and tests to exclude other conditions.

It is important to note: a negative RF or anti-CCP does not exclude RA, and a positive test does not on its own confirm RA. Clinical correlation is essential.

Imaging and other investigations

- Plain radiographs (X-rays): useful to detect joint damage and erosions, but early in disease may be normal.

- Ultrasound and MRI: more sensitive in early disease to detect synovitis, effusion, early erosions.

- Sometimes CT, bone scans, DEXA (for assessing osteoporosis risk) may be used.

Diagnosis criteria and timing

Early diagnosis is critical: joint damage in RA can begin within the first year.

Clinicians often use established classification criteria (such as from the American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) which incorporate joint involvement, serology (RF, anti-CCP), duration of symptoms and markers of inflammation. The focus is increasingly on “treat-early, treat-aggressively” to prevent irreversible damage.

Treatment

Overall goals of treatment

The treatment of RA aims to:

- Relieve pain and inflammation.

- Preserve or restore quality of life – ability to work, perform daily activities.

- Prevent or slow joint damage (erosions, cartilage loss) and maintain joint function.

- Address systemic complications and comorbidities, and reduce overall morbidity and mortality.

Because there is currently no cure for RA, treatment is lifelong in most cases and tailored to disease activity, severity, comorbidities, and individual patient factors.

Medications

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) & analgesics: These help relieve pain and stiffness, but do not prevent joint damage on their own.

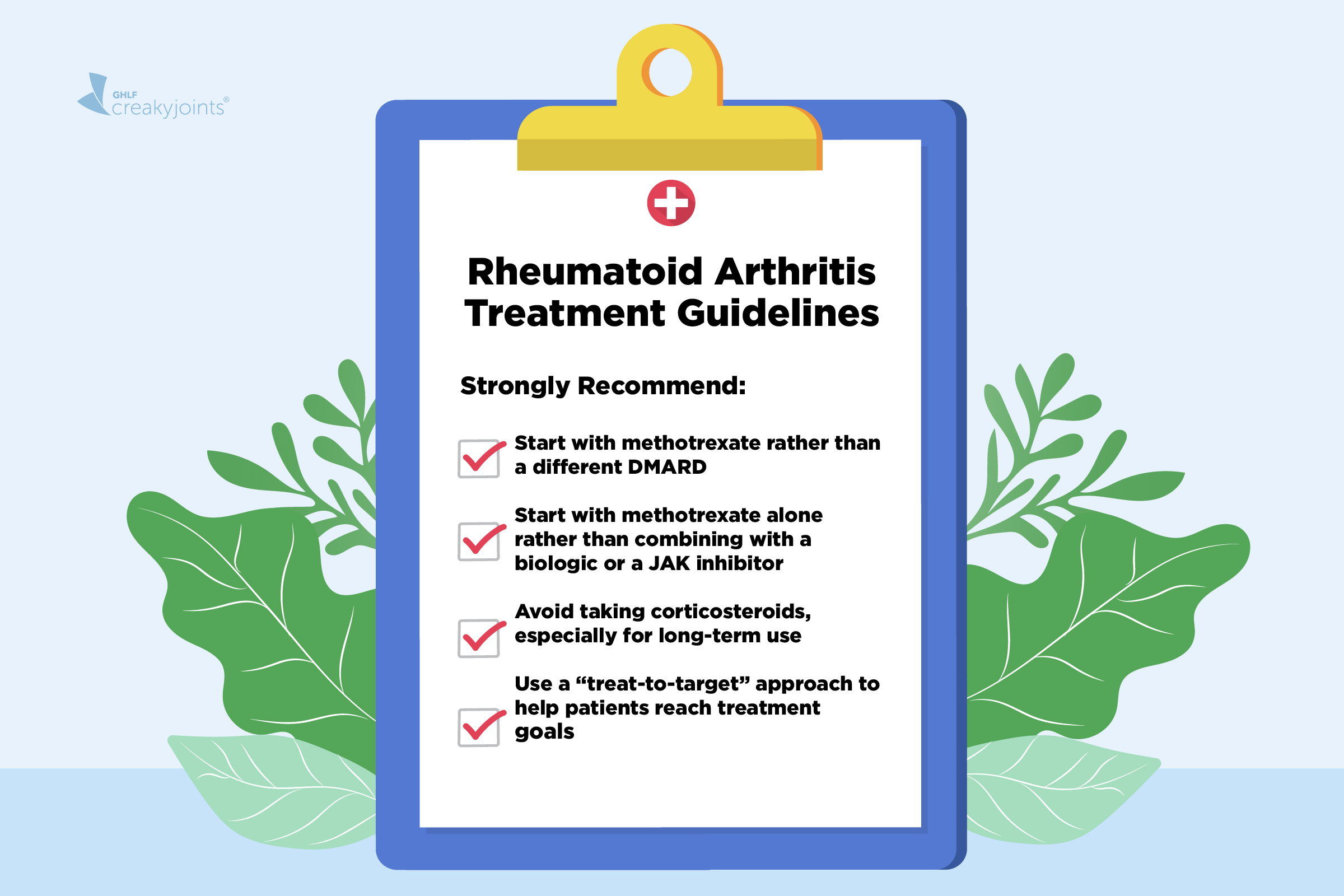

- Glucocorticoids (corticosteroids): Often used for short-term control of flares or bridging therapy until slower-acting medications (DMARDs) take effect. Long-term use is limited due to side-effects.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs): These form the backbone of RA treatment. They work to alter disease course, reduce or prevent joint damage. Examples include Methotrexate, sulfasalazine, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine. Early initiation is strongly recommended.

- Biologic DMARDs and targeted synthetic DMARDs: For patients whose disease doesn’t adequately respond to conventional DMARDs, biologics (e.g., TNF-alpha inhibitors, IL-6 inhibitors) or newer targeted agents can be used. These are expensive and require monitoring.

Non-pharmacological treatments

- Physical therapy and occupational therapy: Exercise programmes to maintain joint flexibility, strength, and function; training in joint protection, assistive devices, energy conservation.

- Lifestyle modifications: Maintaining a healthy weight, smoking cessation, balanced diet, reducing cardiovascular risk factors. These enhance overall outcomes.

- Patient education & self-management: Supporting patients to understand their condition, monitor symptoms, manage flares, adopt healthy behaviors.

Surgical and advanced interventions

When joint damage is severe or functional impairment is high:

- Joint repair, synovectomy (removal of inflamed synovium), joint replacement (arthroplasty) of hips, knees, shoulders.

- Tendon repair, fusion procedures in some cases.

- Monitoring for and treating complications (osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, lung involvement) is part of care.

Importance of early treatment

The concept of a “window of opportunity” is central in modern RA care: initiating effective therapy early in the disease (ideally within first 3–6 months) can markedly improve long-term outcomes, reduce joint damage, increase remission rates.

Delays in diagnosing and treating RA are associated with worse outcomes.

Monitoring and follow-up

Treatment of RA requires regular monitoring of:

- Disease activity (joint counts, patient symptoms, labs).

- Side-effects of medications (e.g., liver function, blood counts, infection risk).

- Imaging to monitor for new erosions or joint damage.

- Management of comorbidities (cardiovascular risk, bone health, lung disease).

Prevention and Risk-Reduction Strategies

While RA cannot always be prevented, especially in genetically predisposed individuals, there are strategies that may reduce risk, delay onset, or minimise severity—and once RA has begun, strategies to minimize progression.

Risk-reduction (primary prevention)

- Avoid smoking: Smoking is a major modifiable risk factor both for developing RA and for more aggressive disease. Promoting cessation is key.

- Maintain healthy weight and exercise regularly: Reducing obesity and systemic inflammation may lower risk and improve outcomes.

- Oral health: Treating gum disease (periodontitis) may be a beneficial adjunct (though evidence is still emerging).

- Healthy lifestyle: Balanced diet (anti-inflammatory diets such as the Mediterranean diet), managing cardiovascular risk factors, regular physical activity.

Early intervention and secondary prevention

- Early diagnosis: Recognizing early symptoms (joint stiffness, small joint swelling, prolonged morning stiffness) and referral to a rheumatologist allows prompt treatment, which can alter the disease course.

- Aggressive early treatment (“treat-to-target” approach): Setting goals (e.g., remission or low disease activity), adjusting therapies as needed to achieve those goals, thereby limiting joint damage.

- Regular monitoring and joint protection: Educating patients on protecting joints, avoiding excessive mechanical stress, using assistive devices if necessary, and ensuring good ergonomics in daily life and at work.

- Vaccination and infection prevention: Because RA and its treatments increase risk of infections, staying up-to-date with vaccinations and managing comorbidities is part of comprehensive prevention of complications.

Tertiary prevention (minimizing complications)

- Addressing osteoporosis risk: Many RA patients are at increased risk of osteoporosis (due to inflammation, glucocorticoid use). Ensuring appropriate bone health monitoring, calcium/vitamin D, and bone-sparing therapies.

- Cardiovascular risk reduction: Chronic inflammation in RA accelerates atherosclerosis, so managing blood pressure, lipids, smoking, diabetes and encouraging exercise is critical.

- Psychosocial support: Dealing with chronic illness, pain, disability and fatigue may lead to depression or anxiety. Support and resources are important for holistic prevention of disability.

Conclusion

In summary, rheumatoid arthritis is a serious and potentially debilitating autoimmune disease that primarily affects joints but has systemic implications. It begins with joint inflammation, especially in small joints, and if untreated may lead to irreversible damage, deformity, and raised morbidity and mortality.

Understanding its symptoms — such as bilateral joint swelling, prolonged morning stiffness, fatigue — is key to early recognition. While the exact causes aren’t completely known, genetic susceptibility plus environmental triggers (notably smoking) set the stage for immune-mediated attack of the synovium.

Diagnosis requires clinical assessment, laboratory tests (RF, anti-CCP, ESR/CRP), and imaging, and must be done early to maximize outcome. The cornerstone of treatment is early initiation of DMARDs (and often biologics), lifestyle optimization, physical/occupational therapy, and monitoring for complications.

Prevention of RA in the strict sense may not always be possible, but risk-reduction (smoking cessation, weight control, oral health) and early aggressive treatment are powerful tools to reduce damage, improve quality of life, and prevent disability.

For anyone experiencing prolonged joint swelling, stiffness (especially morning stiffness), fatigue or systemic symptoms, a prompt evaluation by a rheumatologist is strongly recommended — the earlier the disease is controlled, the better the long-term outlook.

Related Topics

Related Articles

Rheumatoid Arthritis kay Asbab, Alamaat, Ilaj aur Ihtiyaat

رمیٹی سندشوت (Rheumatoid Arthritis) – ایک جامع تعارف رمیٹی سندشوت ایک دائمی (chronic) خودکار قوتِ مدافعتی بیماری (autoimmune disease) ہے، جس میں جسم کا مدافعتی نظام اپنے ہی جوڑوں (joints) کے اندر موجود باریک جھلی (synovium) پر حملہ کر دیتا ہے۔ اس کے نتیجے میں جوڑوں میں سوجن، درد، اکڑاؤ، اور وقت کے ساتھ ہڈیوں […]

Osteoporosis: Haddi Ki Kamzori, Ilaj aur Bachao ka Mukammal Jaiza

آسٹیوپوروسس کوئی اچانک ہونے والی بیماری نہیں بلکہ ایک خاموشی سے بڑھنے والا عمل ہے۔ لیکن اچھی بات یہ ہے کہ اس کا علاج اور بچاؤ ممکن ہے۔ اگر وقت پر تشخیص کر لی جائے اور مناسب غذائی، دوائی اور طرزِ زندگی میں تبدیلیاں کی جائیں تو فریکچر کے خطرے کو نمایاں طور پر کم کیا جا سکتا ہے۔